Eroticism and Sexuality in 16th Century Renaissance Art

- steph markerink

- Aug 24, 2020

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 20, 2021

In a world governed by the conservative hand of the Church, and the societal pressure of maintaining respectability, the role of eroticism and sexuality within 16th century Italian art was complex. On the stage of acceptable Renaissance art there was no space for explicit representations of sexual content. Yet, under the guise of visual metaphors, and mythological tales, combined with the use of innovative technological advancements, the exploration of eroticism was ubiquitous. Michael Baxandall argues in his book Painting and Experience in Italy, that ‘social history and art history are contiguous, each offering necessary insights into the other’1. This statement directly relates to the unavoidable entanglement of the overwhelming control of the Church, and its condemnation of eroticism and sexuality within 16th century Italian art despite the existence of an avid market for this subject. But as we know now and they knew then sex sells, even under the vigilant eye of the Church. The role of eroticism and sexuality within art became one of disguise, where ‘the real purpose of concealment [was] to reveal’2. This essay will deconstruct various methods that Renaissance artists used to encode their works with what has been described as ‘secret eroticism’3. Firstly, the work of Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) will be analysed to decipher common symbols for lust, love and sensuality. Secondly, the representation of mythological narratives as an analogy of sexual desire will be discussed through the works of Titian (1490-1576) and Parmigianino (1503-1540). Further opening a discussion into the representation of female sexuality and homoeroticism. Finally, this essay will examine the significance of the printing press in the distribution and mass production of erotic images, looking particularly the work of Giulio Romano (1499-1546) and Marcantonio Raimondi (1480-1534). Though they may not play the part of the protagonists, eroticism and sexuality are definitely not strangers to the stage of Renaissance art.

With the rise of the Christian Church’s following, wealth, and therefore societal power, the representation of ‘nudity became taboo [and] sexual desire was disparaged’4. Meanwhile, the rise of Humanism and Mannerism within the Renaissance meant that artists and patrons were increasingly interested in evocative, hyper-idealised, and sensual subjects. Thus, artists were faced with a challenge to make ‘lust an intellectual exercise’5 by encoding their works with sexual symbolisms and visual metaphors. This is evident in Andrea Mantegna’s work, Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue, 1502 (Fig.1), which depicts a battle between Virtues and Vices. The most prominent sexual symbolism in this work takes the form of man’s bestial alter ego, the satyr and the centaur6. The hybrid creatures became symbols of lust and unbridled passion within man. In this work, a lustful centaur pursues Venus, the Goddess of Love, with a monkey on his back as the personification of evil7. In addition, a satyr with an erect phallus grasps Cupid in his arms to represent the corruption of innocence and purity. Meanwhile, Pallas, the Goddess of Reason and Wisdom, holds a broken spear, reminding the beholder of the symbolic significance of hunting and its resonance with sexual energy8. However, as the spear is broken it becomes a ‘symbol of victory’9, foreshadowing the triumph of virtue over these lustful, wicked creatures. The significance of this work is not only evident in revealing the depth of encoded sexual language within 16th century Renaissance art, but also in its ability to simultaneously be interpreted as a moralistic work. This work was commissioned by Isabella d’Este to be hung in her studiolo with the ‘purpose of presenting to the world an appropriate image of the noblewoman’10, to ‘give expression to her ideals of culture’11. To restate Robert W. Gaston’s argument in his work ‘Sacred Erotic’, ‘the real purpose of concealment is to reveal, and prudishness is merely a form of repressed lasciviousness’12. Thus, Mantegna portrays lust, sensuality and desire as the villain of Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue, to allow the illustration of such subjects to be justified as a moralizing istoria.

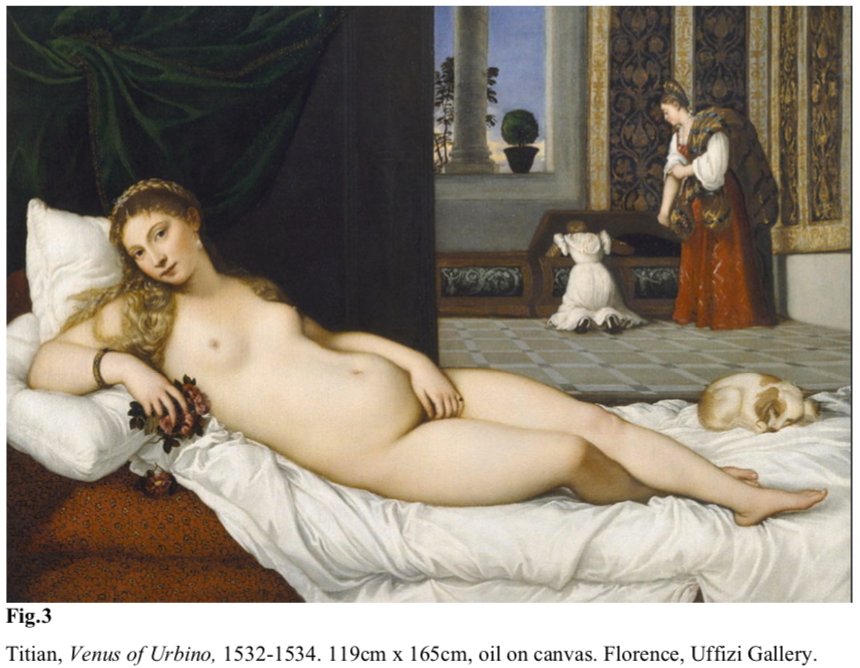

The use of creatures such as the satyr and centaur are also part of a broader scheme, in which 16th century Renaissance artists used the guise of mythological narratives to depict erotic subject matter. Despite the condemnation of nudity and sexuality within art, the sensual, imaginative, and lavish world of the Greek gods and goddesses not only vindicated artists in their exploration of such themes, but also elevated the respectability of their practice13. Thus, a new trend of mythological works depicting highly sexualised subjects arose in 16th century Italy14, some with looser connections to mythology than others. The work, Cupid Carving his Bow, ca.1531-1534 (Fig.2) by Girolamo Francesco Mazzola, commonly known as Parmigianino, exhibits such a trend. A fleshy nude adolescent replaces the traditionally cherubic, mischievous young child15, thus symbolically replacing innocent playfulness with provocative sexual curiosity. Arguably the significance of this painting is not the mythological context but the thematic shift of Cupid’s traditional asexuality into an erotic object. This is similarly evident in Titian’s Venus of Urbino, ca.1532-1534 (Fig.3). The painting depicts a nude woman with her ‘soft and glowering fleshy body fully on display’16; she caresses herself while slyly addressing the viewer with a direct gaze. This voyeuristic painting represents no visual cues that this woman is in fact Venus, with some critics claiming she is ‘simply a nude woman’17. Titian has arguably only labeled this woman as the Goddess of Love only as a means to explore the aesthetic form of the female body18. The frequent representation of mythological subjects allowed artists to freely explore erotic subject matter as well as the naked human form without condemnation from the Church, or 16th century Italian high society.

Beyond the broader exploration of eroticism, 16th century Italian artists began to explore the taboo subject of female sexuality while still under the guise of mythological representation. However, this subject was not explored as means to empower the woman subject but to excite their male beholders. As Margaret Miles stated, ‘the nude in art has been, throughout the history of art, simply a naked woman as an object of male sexual desire’19. This statement directly relates to the various interpretations throughout the Renaissance art canon of the lounging Venus. The work, The Sleeping Venus, 1510 by Giorgione (Fig.4), presents a nude woman sleeping in a picturesque countryside with one hand supporting her head and the other between her thighs. The beholder is told that Venus is sleeping innocently, and as a result the placement of her hand only subtly references self-pleasure, a sinful act in 16th century Italy20. Meanwhile in Titian’s later interpretation (Fig.3), which we have already encountered in this essay, the woman parallels the pose of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus21 but she instead exudes sexual prowess. With a direct gaze she acknowledges her viewer, as she basks in the ‘warmth of her own abundant flesh’22, thus strengthening the reference to self-pleasure. Furthermore, Titian has ‘been to considerable pains to demythologize’23 his Venus by placing her in what seems to be a bedchambers, referencing her more to that of a courtesan than a goddess. The combination of the woman’s direct gaze, her enhanced sexual prowess, and the commonplace context outside the mythological realm, arguably depicts a female subject who holds power over her male viewer24 and is unashamed of her sexuality. Thus with only a slight change from Giorgione’s original image, Titian enhances the works sensuality as a means to examine the sexuality of 16th century Italian women, particularly that of the courtesan.

Similarly to their exploration of female sexuality, 16th century artists continued to use the guise of mythology to venture beyond heteronormativity and delve into the realm of homoeroticism. Within the Italian Renaissance ‘pederastic relations were considered to be a natural stage in the lives of both adults and youths’25. As a result a trend of homoerotic subject matter and themes began and works were commissioned even in the court circles of Northern Italy26. Evident in the previously discussed work, Cupid Carving his Bow (Fig.2), the adolescent Cupid holds a large, erect knife between his thighs, carrying ‘overt erotic and specifically phallic connotations’27. Meanwhile he delicately tramples two books underfoot to signify that ‘intellectual pursuit is vanquished by omnipotent Love’28. The viewer is put in the position of hapless victim, trapped by Cupid’s targeted gaze29, thus giving them ‘at the very least a taste for the homoerotic’30 if not explicitly arousing feeling of sexual attraction. Furthermore, the representation of homoerotic subjects was not always as subtle as in Parmigianino’s work. The most common subject used to represent homosexuality was Apollo who ‘had more male lovers than any other god’31. The work Apollo with a Lover, ca.1520- 1530 by Giulio Romano depicts an ‘explicit scene of sexual activity’32 between Apollo and a young boy. Within this work the erotic contents explores the complex perspective of society on homosexual relations. The beholder is encouraged to ‘calibrate his gaze with that of the woman’33, mirroring the voyeuristic sense of disapproval and fascination that are simultaneously evoked at the discovery of the couple. The role of homoeroticism in Italian Renaissance art was not only to stimulate sexual desire but also to comment on the complexity of society’s simultaneous encouragement34 and disapproval of the subject.

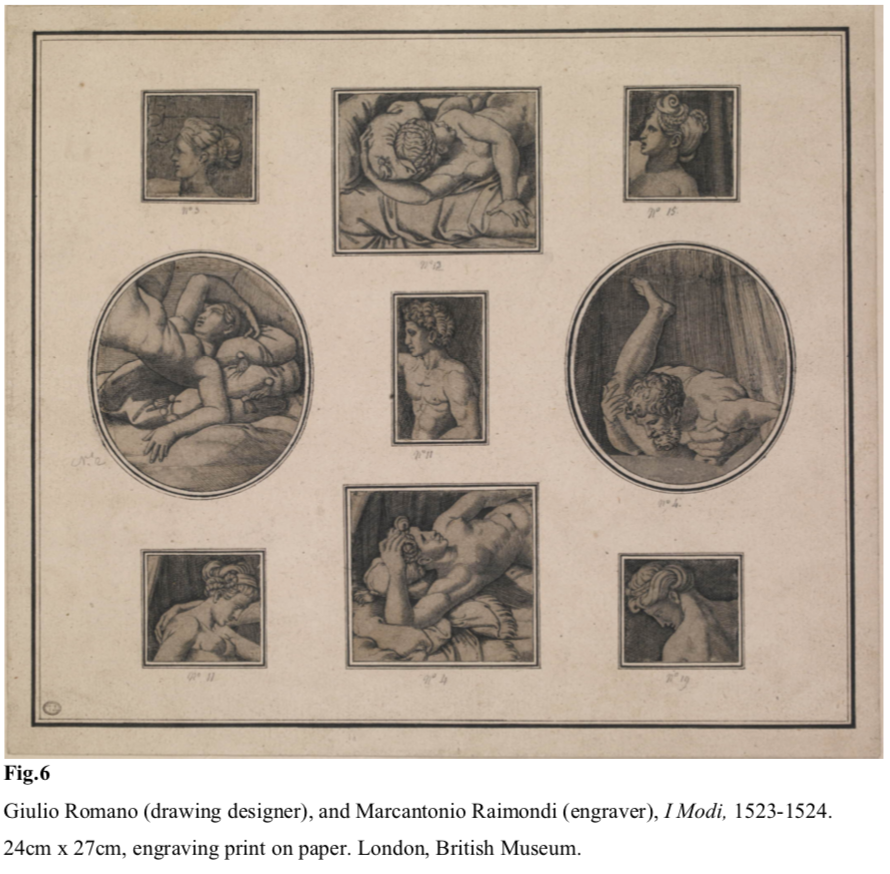

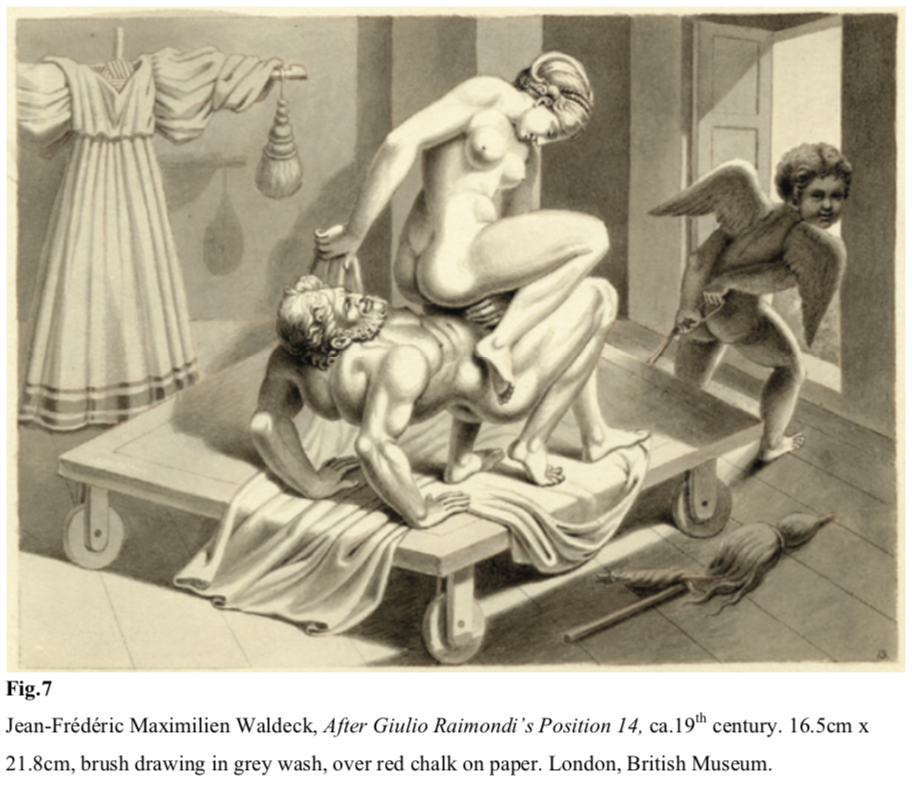

In contrast to the previous works examined in this essay, the introduction of the printing press to Renaissance art enabled the private collection and mass distribution of erotic images, which for the first time didn’t hide behind a mythological facade. The revolutionary print series, I Modi (Fig.6), designed by Giulio Romano and engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi were a set of at least fourteen35 sexually explicit works that caused terrific scandal in Rome36. The prints ‘avoided coded metaphors’37 and instead displayed heterosexual couples in a variety of explicit sexual poses. These were disseminated around Europe as both a pleasurable and educational product38. The prints were progressive in both their technical manufacturing and their scandalous subject matter, with Romano and Raimondi acknowledged as the ‘leaders of design and technique’ of their day39. As seen in Jean- Frédéric Maximilien Waldeck’s remake, After Giulio Raimondi’s Position 14, (Fig.7) the design doesn’t just reject mythological narratives but audaciously satirises them by including Cupid who is completely ignored by the lustful couple. The prints pay tribute to the classical and the contemporary, ‘combining antique tokens, sculptures and reliefs’40 with a daring representation of sexual acts that directly challenge societal conservatism. The representation of explicit sexual scenes was executed in a manner of artistic virtuosity, for it was exactly the ‘dramatic variety of posture, and the innovative mastery of serpentine contrapposto and foreshortening’41 that the artists and patrons of the High Renaissance admired and valued. Unfortunately, despite the immense popularity of these prints Pope Clement VII was enraged by their production and as a result they became outlawed and destroyed42. I Modi series represented the cutting edge technology of the printing press and revealed the widespread market for erotic art and sexual education within 16th century Europe.

In addition to their threat to the sanctity of the Church, I Modi series and print culture ‘was beginning to threaten elite privilege’43. The ability for the printing press to mass produce works that were more financially viable than most other mediums meant that the possession of erotic art spread from the exclusivity of the high courts to that of the working class individual. This new point of accessibility to art in combination with explicit subject matter is what fuelled the outlawing of the I Modi series as it reached the ‘improbable hands of high-ranking clerics and curial dignitaries’44, as well as the hands of ‘a less exalted clientele’45. Only Raimondi was punished and imprisoned on account of the works production. As the engraver it was through his efforts that ‘what should have remained private became public, bringing rapture to the greedy eye’46. Eroticism was no longer protected by the walls of a studiolo or private academy47, and instead was brought to the streets in a medium that lacked the social standing of oil painting or fresco48. Thus, the significance of the erotic prints extended beyond their role as controversial art objects, and bled into a potentially ‘damaging’ role to the hierarchy of 16th century Italian society. However, even with the attempt to eradicate the significant influence of I Modi through prosecution and destruction, the series had created a foundation in printmaking that was unyielding, inspiring future artists to explore similar subjects49. Despite the condemnation of the subject, the exploration of eroticism and sexuality within 16th century Italian art was extensive. Under the guise of symbolisms, visual innuendoes and mythological narratives the role of erotic art became one of intellectual innovation for the artist, freedom of representation to the subject, education and pleasure for its audience, and revolutionary challenge to the conservatism of society. Mantegna’s extensive use of visual metaphors to convey the lust and sensuality of his subjects reveals the depth of the symbolic language utilised by artists and patrons within the 16th century. In addition, the clever use of the moralistic or mythological narrative as a justification for the exploration and representation of erotic subject matter, including taboo subjects of female sexuality and homoeroticism, was utilised by majority of 16th century Italian Renaissance artists of erotic subjects. Finally, the impact of the printing press on the accessibility and response to I Modi series revealed the widespread popularity of eroticism, the curiosity of sexual education and the innovative technological possibilities of the printing press. Overall, the role of eroticism and sexuality within 16th century Italian Renaissance art was one of disguise, education, and innovation. Thus proving the inescapable correlation between social history and art history as artists respond to the innate desires of humanity within the confines of their society.

1 Baxandall, 1988, p.5

2 Gaston, 1995, p.258

3 Gaston, 1995, p.258

4 Posner, 1992, p.357 5 Ruggiero, 2010, p. 5

6 Lurati, 2017, p.242 7 Lurati, 2017, p.248 8 Haughton, 2014, p.72

9 Lurati, 2017, p.258 10 Shephard, 2011, p.684 11 Cartwright, 1907, pp.159-60

12 Gaston, 1995, p.258 13 Posner, 1992, p.358 14 Eaton, 2018, p.482 15 Turner, 2009, p.187 16 Eaton, 2018, p.482 17 Hartt, 1970, p.541 18 Chambers, 2000, p.14

19 Posner, 1992, p.360

20 Lurati, 2017, p.254 21 Hartt, 1970, p.541 22 Hartt, 1970, p.541 23 Hartt, 1970, p.541 24 Zerner, 2004, p.216 25 Haughton, 2014, pp.18-19

26 Haughton, 2014, p.19 27 Turner, 2009, p.187 28 Turner, 2009, p.187 29 Rubin, 2018, p.93 30 Turner, 2009, p.187 31 Haughton, 2014, p.23 32 Turner, 2009, p.190 33 Haughton, 2014, p.78

34 Rubin, 2018, p.100 35 Turner, 2009, p.201

36 Eaton, 2018, p.474 37 Wolk-Simon, 2009, p.54

38 Eaton, 2018, p.474 39 Turner, 2009, p.201 40 Turner, 2009, p.201 41 Turner, 2009, p.201 42 Eaton, 2018, pp.474-475

43 Eaton, 2018, p.469 44 Wolk-Simon, 2009, p.54

45 Eaton, 2018, p.478 46 Wolk-Simon, 2009, p.55

47 Wolk-Simon, 2009, p.55

48 Eaton, 2018, p.478

49 Turner, 2009, p.205

REFERENCES Baxandall, 1988: Matthew Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Italy: A Primer in the Social history of Pictorial Style, Oxford, 1988. Cartwright, 1907: Julia Cartwright, Isabella D’Este: Marchioness of Mantua 1474-1539 (Volume I), Milan: University Press of the Pacific, 1907. Chambers, 2000: Emma Chambers, ‘Flesh and Form’ in Nude: Art From the Tate Collection, Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, pp.13-19. Eaton, 2018: A.W. Eaton, ‘’A Lady on the Street but a Freak in the Bed’: On the Distinction Between Erotic Art and Pornography’, British Journal of Aesthetics, 58, no.4, 2018, pp.469-488. Gaston, 1995: Robert W. Gaston, ‘Sacred Erotic: The Classical figura in Religious Painting of the Early Cinquecento’, International Journal of the Classical Tradition, 2, no.2, 1995, pp.238-264. Hartt, 1970: Frederick Hartt, ‘High and Late Renaissance in Venice and the Mainland’ in A History of Italian Renaissance Art, London: Thames and Hudson, 1970, pp.528-573. Haughton, 2014: Ann Haughton, ‘Mythology and Masculinity: A Study of Gender, Sexuality and Identity in the Art of the Italian Renaissance’, Ph.D, University of Warwick, 2014. Lurati, 2017: Patricia Lurati, ‘’To dust the pelisse’: the erotic side of fur in Italian Renaissance art’, The Society for Renaissance Studies, 31, no.2, 2017, pp.240-260. Paton, 2000: Justin Paton, ‘Body Language: Notes of the Painted Nude’ in Nude: Art From the Tate Collection, Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, pp.22-29. Posner, 1992: Richard Posner, ‘Erotic Art, Pornography, and Nudity’ in Sex and Reason, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992, pp.351-382. Rubin, 2018: Patricia Lee Rubin, ’”Especially good in the front and perfect from behind”’ in Seen From Behind, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018, pp.89-109. Ruggiero, 2010: Guido Ruggiero, ‘Hunting for birds in the Italian Renaissance’ in Erotic Cultures of Renaissance Italy, London: Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2010, pp.4-12. Shephard, 2011: Time Shephard, 'Constructing Isabella d'Este's musical decorum in the visual sphere', Renaissance Studies, 25, no.5, 2011, pp.684-706. Turner, 2009: James Grantham Turner, ‘Profane Love: The Challenge of Sexuality’ in Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009, pp.178-227. Wolk-Simon, 2009: Linda Wolk-Simon, ‘”Rapture to the Greedy Eyes”: Profane Love in the Renaissance’ in Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009, pp.43-58. Zerner, 2004: Henri Zerner, ‘Lady in Her Bath: Portraiture with a Difference’ in Renaissance Art in France: The Invention of Classicism, France, Flammarion, 2004, pp.204-225.

Comments